Without apology or explanation Passive Complicity reposts this from 18 April 2014.

Without apology or explanation Passive Complicity reposts this from 18 April 2014.

School holidays series Part two

by Quentin Cockburn

Whilst trawling the internet for Dalek images, (from which to build our life size fully functional Dalek), we accidentally came upon a You tube video of Colin Furze.

Colin Furze. Might be thirty. He is English, possibly from the midlands and enjoys doing crazy hare-brained things. Dangerously, without a helmet, and invariably dressed in ‘nice pants’ shirt and tie. His colleagues must wear ties also. A tie instills respectability. Colin doesn’t give a hoot about respectability. Colin runs a youtube channel, (you can subscribe) and he demonstrates to all kiddies, how to make a pulse jet, a turbo jet, a rocket propelled skateboard, a flame thrower, a cyclotron, with little more than basic tools and basic materials. The turbo jet made without welding from a toilet brush holder, a second hand turbo unit, spark plug and gas bottle is truly inspiring. Colin Furze is the natural enemy of the contemporary parent. He is almost subversive, and I’m amazed he hasn’t been banned.

He makes it quite clear, “Hey kids, bored with endless consumerism, wasted days in shopping malls?  “Venture outside, collect this hard waste, take it home and convert the everyday object into something sublime and potentially dangerous.” The subtext writ large, is simple; “ Do it yourself”, and have the time of your life.

“Venture outside, collect this hard waste, take it home and convert the everyday object into something sublime and potentially dangerous.” The subtext writ large, is simple; “ Do it yourself”, and have the time of your life.

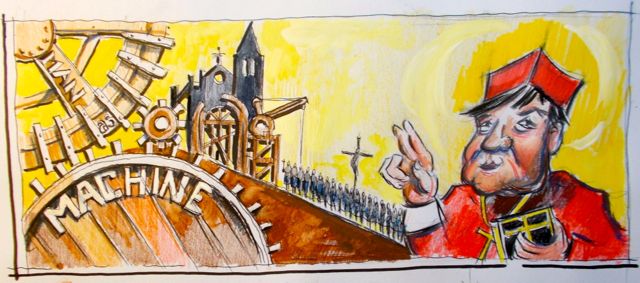

I think it’s because the oldest child amongst us, (myself) has always been fascinated by the simplicity and sheer brutal force that the pulse jet, (power unit for the V1) inspires. It had always been my intention, before arsonists, psychopaths, and misfits had regularly begun the process of burning the Latrobe Valley, to equip myself with a pulse jet, missile body and ramp, and launch it across the Latrobe Valley. I could in one act achieve an apotheosis with ‘Gravity’s Rainbow’

and demonstrate that to all intents and purposes the Satanic Mills of Hazelwood, Australia’s filthiest power station, as the perfect setting to anoint an accursed people with what they really crave, Fear and Victimhood.

The pulse jet powered bicycle or the motorised pram are perhaps the most subversive. The Pulse jet makes a hell of a noise, when hand fashioned, fitted and glows a menacingly deep red. Furze roars across an abandoned air field, (any over-designed soul-less public space will do) on a bicycle with a flaming tail, deafening noise, and just the hint of explosion. He waves and roars in an exstasy of happiness. It’s infectious.

If you subscribe to Furze’ vision, you get all you need to know, but that’s unnecessary, because what Furze has done, (and he deserves a knighthood for this) is to realign the co ordinates, and suggest most emphatically, ‘Life is boring, staid, and predictable’. As a kid you’re unlikely to be handling gunpowder to the mate as you grapple with the Dons off Trafalgar, you are unlikely to stow away, join the circus, take up droving, and get part time work as a test pilot, but you can, if you use a little bit of initiative and a few mates make your own fun and that’s the point. You may blow yourself up, may lose the sight of one eye, be limbless, but as the boy Roger in Swallows and Amazons was taught as they recklessly and dangerously and bravely, set sail for the first time, upon the subject of drowning, “if duffers will, if not wont’. It’s as simple as that.

If you’re a nong, you’ll be selected by Darwin’s law as unfit to proceed, and just as likely to die in all the safe ways we’ve devised since banning everything. In car smashes, airplane pilot psychosis, from trains, trams, dooring, cyber bullying, facebook rage, or synthetic implant collapse.

But you wont die from drugs or the crucifying loneliness of being left alone on the net, watching telly, whilst your parents grind themselves in to dust sacrificing those odd weeks for quality time, when you’d rather they be bludgeoned to death at work.