(The timing of publication of this article is purely co-incidental.)

By Gavan Naden.

There comes a point in every week when I walk out the door and don’t come back.

I leave behind her Scandi interior design, so white and crisp it’s like tunnelling through a snowstorm. Fluffy cushions are piled high on the permanently plumped sofa and an array of colour-coordinated plants cascade out of old teapots and ribboned wicker boxes. It’s a world that looks so pretty you could eat it.

And I leave not because I don’t love her, but precisely because I do. It’s just that I feel living together is so overrated.

Sure, I could get used to it. There are fantastic benefits. She cooks using unpronounceable herbs in Le Creuset pans that only see sausages when it’s my go. My clothes, draped over the back of a chair at night, are never there in the morning and she says strangely alluring things such as, “Do you think that wall would look better emulsioned in Misty Buff?”

When I draw the curtains in her home in leafy Hertfordshire, she waits until I leave the room then re-adjusts the folds. And I have absolutely no idea why. However, I say nothing, distracted by the search for my laptop, which has been silently shifted from my place of work into a far corner. She believes that change is progress. It’s the drug that drives her. So the entire house is painted a marginally different shade each season, otherwise it unbalances her chakras.

To her, the disruption is worth the effort, it brings a joy and puts a spring in her step (I’ve seen her break into song with the arrival of a new lampshade).

I have to admit where once I’d nod and listen with genuine interest, now when she asks what I think of her startling plans it’s all too apparent that I’m staring intently at the loose wire in the plug. Being caught out is my own fault.

But the addictiveness of change dulls my brain. So each week I leave and return to my own flat and we never have to get to that point where it feels like the walls are moving in.

Except the clock is ticking and there is a huge elephant sitting in the middle of her brightly polished living room. My son is 17 and on the verge of heading off to university. So my place in London will soon be seen as surplus to requirements. Can I really justify keeping my own flat that will only be fully occupied during the holidays?

But my flat represents far more than some random I’m-an-independent-man bolt hole. There’s a fencing foil on the wall, doors that don’t quite fit and a bike hanging from the ceiling. There’s a sofa no one sits on, which is only there to fill the gap between my speakers. Geezer chic.

And when I walk out my door, on the horizon the haze of London shimmers in all its noisy, dirty glory. The Shard rises like a glinting unfinished arrow, there’s the stench of diesel, and Crystal Palace supporters yelling (strangely, when I mention these marvellous benefits, she looks decidedly nonplussed).

After years of responsibilities, bringing up children and watching over pet goldfish, I had assumed that this would become my time. I was on the verge of a breakthrough and newfound freedom when I could flamboyantly toss a teabag into the sink, where it could sit happily untouched for days. No more early morning dash to the school bus stop, or late-night pickup from the cinema. It would be a time free of mental anguish when I could sit back and rebelliously eat a meal for one, microwaved to perfection in under five minutes. I was, I assumed, about to enter Shangri-la.

But she wants us to throw it all in and head off to the coast together. Sell up so we can see grey crashing waves and walk along drizzly beaches. Open spaces leading to no fixed point make her stride with real purpose. That’s when she really smiles, places a hand to her ear and says, “Hear that?” I cautiously shake my head. She gives me a seductive smile and yells, “Exactly!”

Yet even if I squint all I can see is a mass of endless green leaves and trees blocking my view. And sometimes all that silence gives me a headache.

Living under the same roof would not prove we are any stronger, it’s not a panacea to the perfect relationship. Breathing the same air all the time can take the edge off its freshness.

Fine, we can be together all the time on holiday. The odd week away, I understand. It’s a nice break from the norm. We’ve even cycled the length of Cornwall and climbed Snowdon. I can see the point of that. There is a sense of achievement, of shared moments, which are fabulously bonding. But to idly wander the byways of some nondescript coastal eternity for ever doesn’t quite do it for me.

The truth is I don’t really want to live with her, certainly no more than I want to eat steak and chips each night. It’s a road I’ve already pedalled and fallen from, and there is something freeing about love when you have somewhere else to go.

When I appear perturbed or confused as we scroll through fine-looking properties with Agas and open fires on housing websites, she gets frustrated. She claims I’m damned awkward. In fact, I am just perturbed and confused. It’s not that I am being deliberately uncommunicative, rather I struggle to find the right words to justify indifference.

How am I to engage in a conversation about a place I’m having to view via a fisheye lens? “Nice” is to condemn it with faint praise and “excellent” is the equivalent of Hugh Grant sarcasm.

She raises her eyebrows, saying it’s obvious I don’t notice my surroundings and that all those delicate finishing touches don’t matter to me. “Life is about change,” she says. “It’s time to stop dressing like a gap-year student and start making plans.”

The trouble is, she thinks she knows me rather well and believes the finer things in life will pass me by. That’s where she’s wrong, of course, as she is one of the finer things in my life and I love her all the more because of our differences and the fact that we’re not together all the time. But that’s a hard sell.

Inhabiting the same property makes perfect sense in lots of ways. It would save a fortune on disposable toothbrushes and I would no longer arrive wearing a rainproof baker boy cap during an unexpected heatwave. I wouldn’t have to load my Oyster card or have one eye on train times. It would mean an end to that joyful moment when you say hello, a slice of life that never becomes stale. But that all sounds rather lame.

If we threw it all in and headed off into the sunset, the one thing that would remain the same would be us. And what would become of my rather strange paintings? She might not like them. Blimey, come to think of it even I don’t like them.

Now whenever I walk out the door it gets more scary with decision time another week closer. I’m edging nearer to that moment when I should commit, make up my mind and move on with life. All this potential freedom is proving to be a pain.

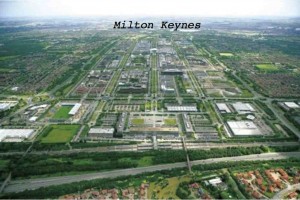

In the early 90s, Milton Keynes ran a saccharine advert featuring a little boy peering wistfully out of a car window while leaving a horrid, noisy city. He was delighted by all the exciting things he was seeing – clouds, cows, trees. It ended with the slogan, “I wish I lived here.” Because I guess they don’t have clouds and trees in the city. Or maybe the grass is always greener, even when it’s actually AstroTurf.

In the early 90s, Milton Keynes ran a saccharine advert featuring a little boy peering wistfully out of a car window while leaving a horrid, noisy city. He was delighted by all the exciting things he was seeing – clouds, cows, trees. It ended with the slogan, “I wish I lived here.” Because I guess they don’t have clouds and trees in the city. Or maybe the grass is always greener, even when it’s actually AstroTurf.

I try to imagine living together but all I can see is a lonely bloke on a windy beach with a metal detector, a long way from Brixton Academy.

My mind just doesn’t do Misty Buff.

From The Guardian 22 August 2014