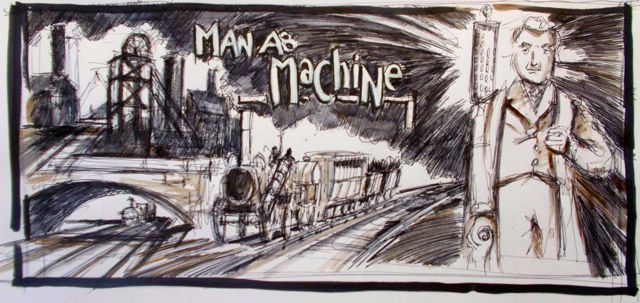

Tarquin O’Flaherty opens a series on the import of George Stephenson. This continues on the general theme of ‘Trains’, where in the last post the role played by navvies was discussed.

In 1781 the British general Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown and American Independence was guaranteed. The King of England, George the Third, being marginally unhinged, had developed the habit of talking to trees. The Tory government of twelve years was about to be kicked out and George Stephenson was born nine miles west of Newcastle-on Tyne, North East England, in the village of Wylam on the 9th of June.

It seemed unfair of me to celebrate the railway navvies and not give George Stephenson and his contribution to railway locomotion its proper due. Stephenson was born into that fateful period where Europe was being devastated by the Napoleonic wars, when horses and feed were fetching astronomic prices and the Industrial Revolution was gathering pace. Because of increasing industrialization, all through the 18th century, creative engineers had been playing around with steam as a source of power to drive pumps. Mines were notoriously prone to flooding and an alternative to the power of horse driven pumps was becoming more and more urgent.

The notion of introducing steam into an enclosed space, then allowing the steam to condense so as to create a vacuum was well known. A vacuum pump invented by Thomas Savery,(1650-1715) roughly on the principle of a coffee syphon, and using the vacuum to draw water from mines was tried but found to be inadequate. The idea of using a piston was introduced by the French physicist Denis Papin (1647-1712), inventor of the pressure cooker, when he demonstrated the principle that steam could move a piston in a cylinder. Unfortunately he took the idea no further.

Working with these two ideas, a steam pump, used extensively to pump water from mines, was invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, approximately 60 years before Stephenson was born. In 1782, the brilliant James Watt, incorporating Newcomen’s design ideas, came up with a stationary steam engine with winding wheels, which, using either ropes or cables, could be used, from a stationary position, to haul heavy loads.

It had been long established in the mining industry that carts or wagons, with flanged wheels and mounted on wooden railway lines, allowed horses to pull much heavier loads than if they’d been on the road.

Ten years before Stephenson’s birth, Cornishman Richard Trevithick, inventor of the first steam locomotive, was born in 1771. Suffice it to say that he very soon became Watt’s rival in the production of stationary steam engines. He completed his first locomotive in 1801 which ran (briefly) on the road. Somewhere in Cornwall the steering mechanism collapsed, the locomotive took off, out of control and crashed heavily into a house.

This is what Davies Gilbert, one of Trevithick’s friends recorded of the aftermath of the crash:

‘The parties adjourned to the hotel and comforted their hearts with roast goose and proper drinks when, forgetful of the engine, its water boiled away, the iron became red hot, and nothing that was combustible remained, either of the engine or the house.’